A potential employee’s guide to Silicon Valley startup equity

You’re done your interviews, and you have a few Silicon Valley startup offers in-hand. The offers have a bunch of numbers and you’re not sure how to put them all together. You’re bombarded by terms like ISOs and NSOs and vesting period and cliff and strike price and fair market value that you don’t really understand, but owning 0.1% of the company sounds great in theory, so you go to sign on the dotted line.

Pause. Subtle differences here can have massive downstream consequences. If you’re unaware of some of these policies, you might end up paying $100,000+ more in taxes than you anticipated, or be forced to choose between staying at a job you don’t love and leaving potential millions on the table.

Back in 2012, I was at a conference called CUSEC. At the post-conference happy hour, an Engineering Manager at Twitter named Ian Chan took a bunch of us aside. He told us he was going to tell us something that could potentially save us a ton of money if we ever joined a startup. He proceeded to explain what an 83(b) election is, and he was right — it did and will save me a ton of money. I’d like to pass that knowledge on to you.

This post is going to focus on a narrow but common set of circumstances for employees at early startups (usually <$1B valuation). We’ll assume that the equity part of the offer is for incentive stock options (ISOs), rather than restricted stock units (RSUs), or actual stock if it’s a public company. Companies usually move from ISOs → RSUs → publicly tradable stock as the company grows. This guide is exclusively for ISOs. Since tax implications are important here, and taxes are specific to your locale, this post is also specifically references American taxes.

DISCLAIMER: I have zero professional experience in tax or law. I’m an early software engineer at Figma (company was ~20 people when I joined). Do not use this post as a tax calculator! Use this post a tool to ask better questions to well informed people about potential outcomes.

The standard deal

A standard deal for an early startup in the valley looks something like this:

- X shares

- Strike price of $Y

- 4 year vest, 1 year cliff

To make calculations easier for the rest of the post, I’m going to use the following semi-realistic numbers:

- 20,000 shares

- Strike price of $0.30

- 4 year vest, 1 year cliff

Let’s take a look at what each of these terms means.

20,000 shares: Your offer letter might say something like “Subject to the approval of the Board, you will be granted an option to purchase 20,000 shares”. This 20,000 is the number of shares from the company you’ll eventually be allowed to buy. This is similar to the # of shares you might buy of a public stock, except that you won’t be able to freely buy and sell these shares whenever you want to.

Strike price of $0.30: The strike price is the price you’ll pay per share to purchase. So if you want to buy 7,000 of the shares and your strike price is $0.30, then you’ll need to give the company 7,000⨉$0.30=$2,100. Crucially, as the value of the company increases (hopefully), this price does not increase. If the company increases in valuation from $1M to $50M between when you join and when you purchase, you still only pay $2,100, not $105,000. This increase in the value of the shares without an increase in the price to purchase is the whole point of stock options.

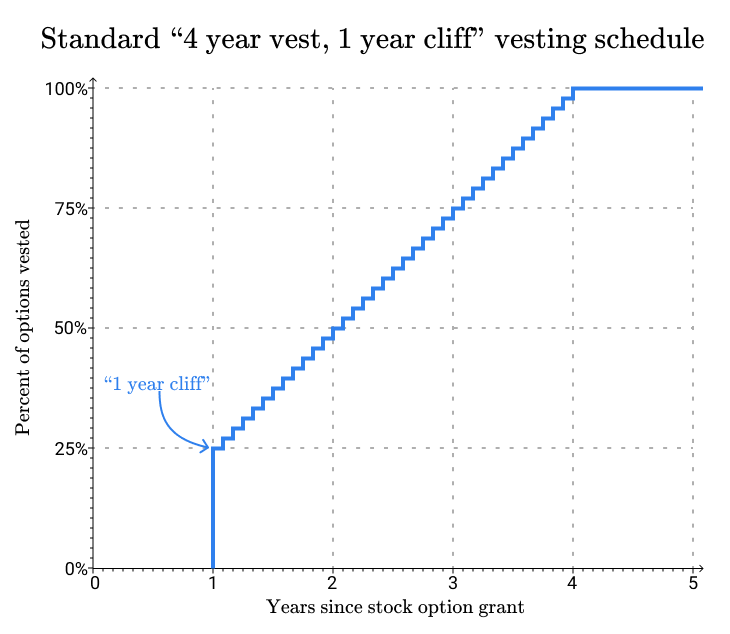

4 year vest, 1 year cliff: This is a standard “vesting schedule”. In simplest terms, this means if you stay for 4 years, you have the right to purchase the full number of shares, and if you stay for less than 1, you leave with nothing.

In more subtlety, it means that at the 1 year mark, you gain the right to purchase 1⁄4 of the total agreed upon share count (20,000/4=5,000). Every month after that, you’ll be able to purchase 1⁄48 of the remaining shares (20,000/48=416).

Once you hit each vesting date, you aren’t required to purchase. As long as you’re employed at the company, you have right to purchase any shares you’ve already vested.

It’s worth mentioning that many companies do an equity refresher program, where employees are granted additional equity after they’ve been at the company for a while. This is important to mitigate their total compensation decreasing dramatically once they’ve completed vesting their initial grant.

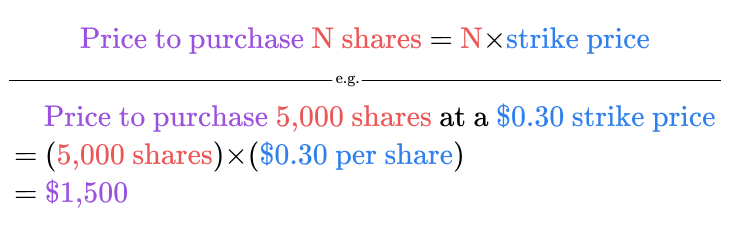

Time to purchase the stock

You’ve made it to your 1 year cliff! Congratulations! You’ve earned the right to purchase some of the company stock. Purchasing the stock is called called “exercising the option”. Since you have a four year vesting schedule, you now have the right to exercise 1⁄4 of your options. In the above offer, this allows you to purchase 20,000/4=5,000 shares. The purchase cost here is easy to calculate. It’s just the # of shares times the strike price. 5,000⨉$0.30 = $1,500.

But what about the taxes? Taxes can create an extremely employee-hostile situation here.

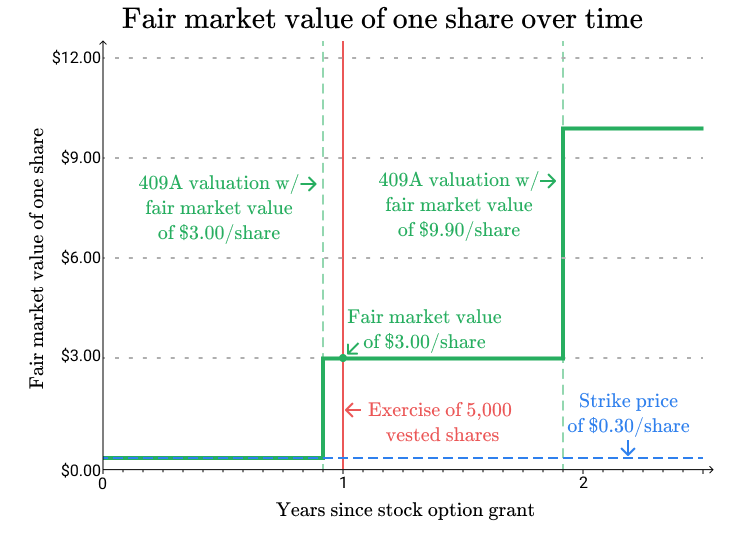

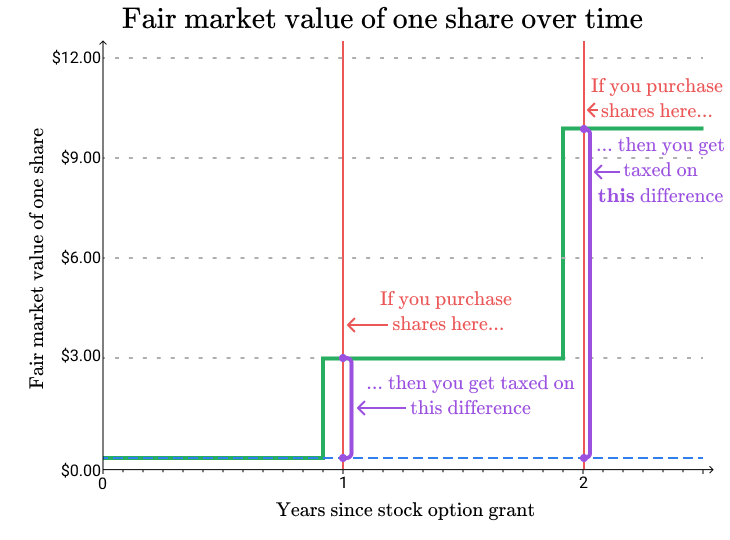

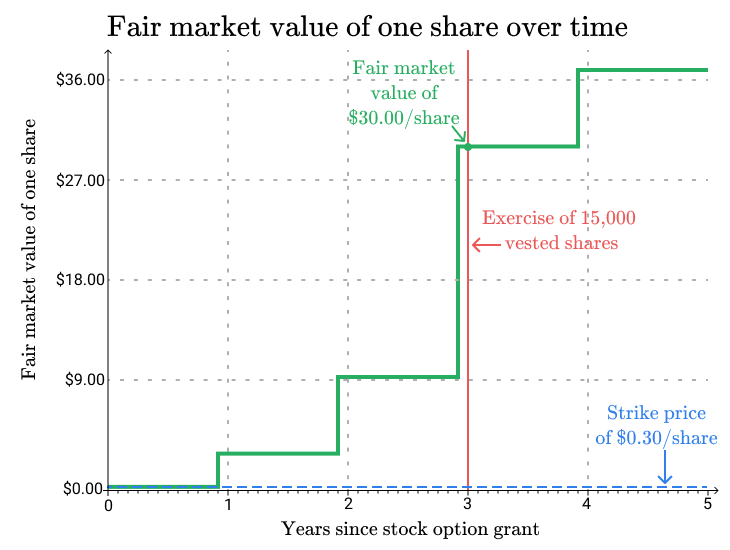

Let’s say that your company has been absolutely crushing it, and since you’ve joined, the company has increased its valuation 10x from $1M to $10M. The valuation that’s relevant here is called the “fair market value” or the “409A valuation”, which is sometimes different than the valuation in press releases about venture capital fund raises. Companies are required to get a new 409A valuation at least once every 12 months.

While you paid $0.30 per share, since the company has increased its valuation 10x, as far as the IRS is concerned, those exercised shares are worth 10x as well. So they’re worth $3.00 per share now. This sounds great until you realize that the IRS wants to tax you on the difference between those two amounts.

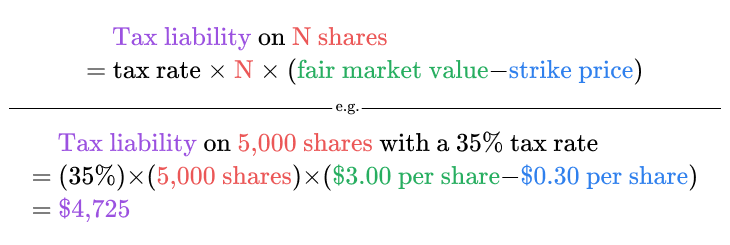

The exact tax details here are complicated, but the crucial thing is that you can get taxed by this thing called AMT (Alternative Minimum Tax) on the difference1. Since we’re mostly interested in ballpark figures here, we’ll assume an AMT rate of 35% (28% Federal + 7% California State).

This means you’ll pay around (35%)⨉(5,000)⨉($3.00-$0.30)=$4,725 in taxes on top of the purchase price you pay to the company.

This brings your new total cash needed to $1,500+$4,725=$6,225. Notice how the taxes here are way more than the purchase price itself.

Now you might think “okay, well, that sucks, but I guess I can sell off some of my shares to cover the taxes on it”. Except you can’t. Even though you’ve earned the right to purchase the shares, there’s no legal market to sell the shares yet. So you can’t sell them. The shares are “illiquid”. So you’ve been heavily taxed on an asset that you can’t sell, and that might be worth $0 if the company goes bankrupt before you have any chance to sell.

Given that, a reasonable strategy might be to just hold onto the options until you can convert the shares into cash after you buy them. At that point, you will be able to sell shares to cover the taxes.

Time to quit

Given the scary tax treatment, you decide to wait to exercise. You just hold onto the options instead. You’ve now been at the company for 3 years, and you just got a really tempting offer from another company, so you’re considering quitting.

You might hope that you can just continue holding on to your stock options after you leave until the stock becomes liquid, but in many cases, you’ll be sorely disappointed.

Every stock option agreement will have what’s called a “post-termination exercise window”. This is the amount of time after you leave in which you’ll still be allowed to exercise your stock options. After this window closes, you forfeit all un-exercised stock options. The standard post-termination exercise window is only 90 days.

This leaves you with a choice between three crummy strategies:

- Forfeit your equity

- Pay heavy taxes on an illiquid asset that might ultimately be worth $0

- Stay at the company, and turn down the other job offer

The same calculation as before applies to the exercise strategy, but just to lay it out, let’s assume the company has continued on a rocket trajectory and now has a fair market valuation of $100M, yielding a new fair market share value of $30.

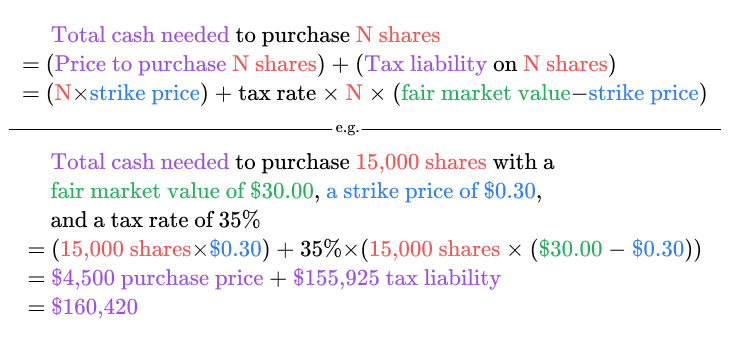

You’ve now vested 3⁄4 of your stock option agreement, allowing you to purchase (3⁄4)⨉20,000=15,000 shares for 15,000⨉$0.30=$4,500. But the IRS now thinks these shares are worth $30.00 each, for a total value of 15,000⨉$30.00=$450,000.

Your AMT tax liability now becomes ($450,000-$4,500)⨉35% = $155,925. So the total amount of cash you need to put in to claim these shares becomes $4,500+$155,925=$160,420. This might be way more cash than you can afford to put in.

This situation is what people sometimes refer to as “golden handcuffs”. Given that their choices if they quit are “spend a ton of money on something very risky” or “walk away with nothing”, many people will simply stay until the company IPOs, even if they’d rather quit.

Avoiding the golden handcuffs

There are two main ways I know of which allows employees to avoid this situation: long post-termination exercise windows, and early exercise. These are both policies that companies may or may not offer to employees, so you should ask about them when considering your offer!

Long post-termination exercise window

Rather than 90 days, some companies offer much longer exercise windows. Figma has a 5 year window for all employees with a tenure of over 2.5 years. Coinbase has a 7-year post-termination exercise window for all employees with with a tenure of over 2 years. Pinterest had 7 before they IPO’d.

A 5 year post-termination exercise window means that you can leave the company and hold onto your options for up to 5 years after you leave. If any time during that 5 years the company’s shares become liquid, you’ll be able to exercise your options, buy the shares, and sell off some of them to cover your taxes. If, any time during that 5 years, the company goes bankrupt, you avoided spending any of your own money purchasing & paying taxes on an asset now worth $0.

There’s some subtlety here where the options change from ISOs to NSOs if you do this, which I won’t go into detail for. See the “ISO and NSO tax treatment” section of this blog post by Carta to learn more. At a high level it sounds like gains from ISOs are taxed as capital gains, and NSOs are taxed as income.

Early exercise

Another way to avoid the golden handcuffs problem is allow employees to purchase shares before the options are vested. Under an early exercise program, employees can purchase up to their entire grant immediately. If you leave the company before your vesting is complete, the company has the right to buy back the unvested shares at either the strike price or the current market value, whichever is lower.

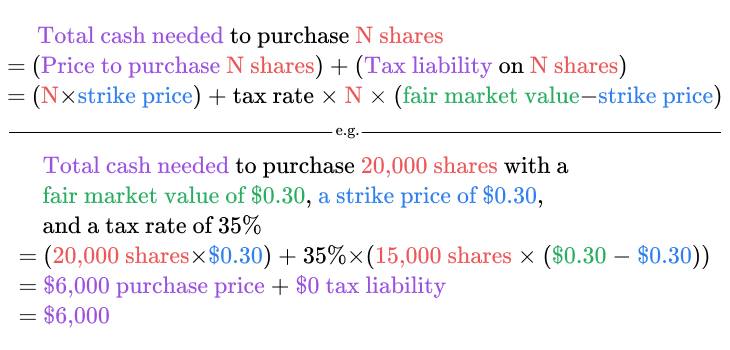

So let’s say that you’ve just joined a company with the same 20,000 stock option, $0.30 strike price, 4 year vest, 1 year cliff stock option agreement, but that also has early exercise available.

You opt to exercise the entire agreement immediately. You pay 20,000⨉$0.30=$6,000 to the company immediately. To make this beneficial, you also need to file a form with the IRS called an “83(b) election”. This roughly tells the IRS that you want to be taxed on the equity now rather than when the stock options vest. You have to file your 83(b) within 30 days of exercising. Don’t mess this up.

What about the AMT? Well, you pay the difference between the current market value and the strike price. Assuming you exercise as soon as the company board sets your strike price, the difference should be zero, because the strike price is set at the fair market value! So if you get the timing right for this, you pay $0 in taxes at the point of exercise.

You still will get taxed on capital gains when you eventually sell the shares, but at least you can avoid getting taxed on the asset when it’s illiquid.

The downside of this is that you’re giving the company money to purchase an asset that might go down to zero at the point in time where you have the least information (the beginning). The upside is that you have no golden handcuffs! Whenever you choose to leave, you walk away with all of the equity you’ve vested to date without paying a dollar more.

Even if your company doesn’t have early exercise available when you join, it’s still worth discussing. Figma did not offer early exercise when I joined, but adopted the policy before the next 409A valuation, so I was still able to take advantage of it.

Even if you’ve had a new 409A valuation since your strike price was set, it’s possible that the difference between the fair market value and your strike price are still small enough that the tax liability is small, making early exercise still worthwhile.

Qualified Small Business Stock

There’s a more subtle benefit of exercising early if the company has gross assets under $50M: the stock may be considered Qualified Small Business Stock (QSBS). If it is considered QSBS, and if you’ve held the stock for 5 years or longer at the point of sale, then you’ll pay 0% capital gains to the IRS during that sale.

To see how much this matters, let’s say that the company IPOs 4 years into your tenure. It does well in the market, and 5 years after your start date, you decide you’d like to sell everything at the current price of $40. You have your entire stock option grant of 20,000 shares vested and exercised now, so the gross sales here will be 20,000⨉$40=$800,000, and the price paid was your strike price times the number of shares, so 20,000⨉$0.30=$6,000. For non-QSBS shares, you’ll be taxed federal capital gains, which is going to be at least 15% and possibly more. ($800,000-$6,000)⨉15%=$119,100. For QSBS shares, you pay no federal capital gains2, so you save that entire $119,100! You’ll likely still owe state capital gains taxes, which can still be hefty, but you have to pay that regardless.

Questions you should be asking

If you’re weighing your different offers, here are some questions you should be asking about the equity to make sense of this. Each of these things is unlikely to be in the offer letter.

- How long is the post-termination exercise window?

- Is early exercise available? If not, why not? It’s possible the founders are unaware of this kind of policy existing, and would be happy to offer it. You can pitch it as a recruiting benefit to you and future potential employees. You can also push for this policy change even if you’ve already joined.

- What is the strike price?

- What do you think the total growth potential of the company is from current value? 10x? 100x?

- What is the total number of shares outstanding? This is the “denominator” to think about when trying to understand what your number of shares means. This will let you calculate your % ownership of the company (ignoring dilution), which will help you gut check the maximum value of your shares assuming the company does really well.

Before I signed my Figma offer in 2016, Figma’s CEO Dylan Field said something akin to “do your financial planning assuming this equity ends up being worthless”. All of the examples in this post are incredibly optimistic, so keep in mind that everything could still hit zero.

Plan for the worst, hope for the best, and do the math.

Further reading

Carta, a company which manages startup equity, has similar guides with more details but less emphasis on how you can get screwed. They include descriptions of ISOs & NSOs and dilution which I skip in this post.

- Equity 101 part 1: Startup employee stock options

- Equity 101 Part 2: Stock option strike prices

- Equity 101 Part 3: How stock options are taxed

- What is a 409A valuation?

Thanks to Rudi Chen and Kevin Lau for feedback on drafts of this post, to Ian Chan for making me think about this in the first place, and to Julia Evans for writing a similar post about stock options which I’ve sent to a ton of people to in the past. Handcuffs Vector by Vecteezy.

- The rough gist of AMT is that it’s a completely parallel taxation structure to regular taxation. You calculate your tax liability under the regular rules, then calculate it under AMT, then you have to pay the maximum. As far as I know, the illiquid gains from your stock exercise are taxable only under AMT, so it’s possible that the taxation on the stock gains might be enough to make AMT more than your regular taxes. If, however, your gains are smaller, then it’s possible you won’t get hit by this because your regular tax might still be more than AMT, even after our stock gains are considered. In that situation, you effectively don’t pay tax on the stock gains at the point of exercise. [return]

- There are limits to the exemptions on your capital gains ($10M or 10x your investment, whichever is greater). If you actually hit this limit, congratulations! Your taxes are probably much more complicated than mine 😅 [return]